Overview: What is a pneumothorax?

A pneumothorax means that air has entered the pleural cavity. As this removes the negative pressure that normally prevails in the pleural cavity, the lung can partially or completely collapse. The pleural cavity is a virtual space between the two layers (“sheets”) of the pleura:

- inner lung membrane that envelops the lungs (visceral pleura or pulmonary pleura)

- Outer pleura that lines the inner wall of the chest (parietal pleura)

There is a small amount of fluid in the pleural cavity so that the two pleural sheets can move against each other without friction and the negative pressure prevailing there causes the lungs to be stretched in the chest cavity. The lungs thus follow the breathing movements of the chest.

If air accumulates in the pleural cavity during a pneumothorax, the negative pressure is released, the lung partially or completely collapses and respiratory function is restricted. The word pneumothorax translates as “air in the chest” (from “pneuma” = air and “thorax” = chest)

Pneumothorax – frequency and age

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs without any apparent cause in people whose lungs are actually healthy. If no cause can be found, it is referred to as “idiopathic”. Typically, young, slim men, but also women, especially between the ages of around 15 and 35, are more likely to develop this form of the disease.

Spontaneous pneumothorax is significantly more common in men than in women. About 2.5 in 10,000 men are affected, but only 1 in 10,000 women. General practitioners have to reckon with approximately one affected person per year in their practice.

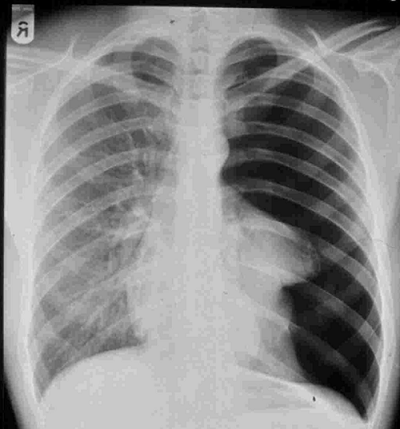

Total collapse of the left side of the lung in the sense of a pneumothorax in a standing X-ray using the a.p. technique.

Pneumothorax: causes and risk factors

A pneumothorax can have various causes. However, there are basically two ways in which air can enter the pleural cavity:

- From the outside: This can be caused by an accident (trauma)(traumatic pneumothorax). Examples: Stab or gunshot wounds, open rib fracture after a fall or medical interventions (e.g. catheter, pleural puncture, surgery).

- From the inside: The air enters the pleural cavity through a tear in the lung. This is usually caused by existing lung diseases, but can also be triggered by a traumatic rib fracture that injures the lung, a diving accident or overpressure ventilation.

Primary and secondary spontaneous pneumothorax

We also make another distinction in pneumothorax:

- Primary spontaneous pneumothorax: The disease occurs suddenly, without warning and without external influence, without any recognizable cause – this is the most common form. In most cases, small air sacs (alveoli) burst in the lungs and air enters the pleural cavity. The most important risk factor for this form of pneumothorax is smoking. Almost 90 percent of patients with a primary pneumothorax are smokers. In women, smoking increases the risk of pneumothorax by a factor of 9, in men by a factor of 22. Lean, tall people under the age of 40 are often affected – however, there is no actual lung disease on imaging.

- Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax: The causes are pre-existing lung diseases. They damage the lungs over time and eventually the alveoli can burst. Possible diseases include emphysema (“over-inflation” of the lungs), bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(COPD), lung cancer, lung abscess, infections of the lungs (e.g. tuberculosis), hereditary cystic fibrosis or, rarely, endometriosis (catamenial pneumothorax). Smoking is an important risk factor for some of these lung diseases. People in middle and old age are usually affected by secondary spontaneous pneumothorax.

Tension pneumothorax – life-threatening complication

A tension pneumothorax (valve pneumothorax) is an emergency that requires immediate action. The disease is life-threatening because the excess pressure in the pleural cavity causes the heart to shift to the healthy side, compressing the large veins leading to the heart. The venous return to the heart is interrupted (or reduced) due to the compression, resulting in cardiovascular shock. A tension pneumothorax is a lung or chest wall injury that pumps air into the chest when breathing in. A valve mechanism in the defective tissue allows air to enter the pleural cavity with every breath, which can no longer escape – so the cavity continues to fill with air. The resulting excess pressure causes the lungs to collapse and the space between the lungs (mediastinum) with the heart is shifted to the healthy side. The situation is most likely to become dangerous when patients are ventilated, as air is pumped into the lungs under pressure through the breathing tube during ventilation.

Symptoms and diagnosis: Pneumothorax often causes shortness of breath

The symptoms of a pneumothorax can vary in severity. The decisive factor is how much air has entered the pleural cavity, or how much the lung has collapsed. Some experience only minor symptoms (see below), which are barely noticeable and not very specific, while others develop life-threatening conditions when the patient’s lung capacity is restricted or the lung collapses completely.

The following signs may indicate a pneumothorax:

- Shortness of breath that starts suddenly – up to the feeling of suffocation

- Accelerated breathing (tachypnea)

- a slight feeling of pressure or pain in the chest – sometimes occurring at intervals, and may also radiate to the shoulders, arms, head or back

- Dry cough, which can be painful

- Blue coloration of the skin (cyanosis) if the shortness of breath is severe and the lack of oxygen in the blood is high

- Skin emphysema: Air accumulates under the skin when an injury is the cause of the pneumothorax. If you press lightly on the skin, you will feel a crackling or crunching sensation, as if you were compressing snow.

- Tension pneumothorax: Further symptoms are added: first a rapid heartbeat (palpitations, tachycardia), then a slowed heartbeat (bradycardia), a drop in blood pressure (hypotension) and increasing breathlessness – the condition usually worsens quickly and there is a risk of acute cardiovascular failure. If you do not intervene immediately and provide pressure relief, many of those affected will not survive. Ventilated patients are particularly at risk.

The diagnosis is made by clinical examination or radiologically; a CT scan may be useful in secondary pneumothorax.

Pneumothorax: prevention, early detection, prognosis

The most important measure you can take to prevent pneumothorax is to avoid inhaled noxious substances such as smoking, marijuana or other inhaled drugs.

Quitting smoking is medically recommended for smokers to prevent a relapse. Because if you continue to smoke, the risk of recurrence four years after the first pneumothorax is 70 percent. If you manage to stop smoking, the risk drops to 40 percent.

You can also prevent pneumothorax if you have existing lung diseases, such as bronchial asthma or COPD, treated promptly and adequately.

There are no special measures for the early detection of a pneumothorax. However, you should always consult your doctor promptly if you experience symptoms such as shortness of breath or chest pain. This is how you find out what is behind the complaints.

Course and prognosis of pneumothorax

The course and prognosis of pneumothorax are favorable in most cases. Spontaneous pneumothorax usually heals within a few days (up to weeks) without any consequences. However, there is a certain risk that the pneumothorax will recur (recurrence). Surgery, which is recommended for a first recurrence of the clinical picture, achieves very good results – the risk of a pneumothorax forming again on the treated side is significantly reduced. You can then go back to your normal everyday life, work or do sport.

Pneumothorax: treatment depends on the extent

The treatment of pneumothorax depends on the underlying cause, the extent of the lung collapse and the severity of the condition. However, the symptoms a patient has also play an important role in the choice of therapy. A primary spontaneous pneumothorax without an identifiable cause, which occurs for the first time and is small, is usually treated without surgery, but at best with a drainage. Patients remain in hospital for several days and we check the pneumothorax at close intervals using clinical and X-ray examinations. We observe how the disease develops. The body usually absorbs the air in the pleural cavity itself within a few days and the pneumothorax heals without complications. Sometimes we administer additional oxygen to promote this process.

In case of a surgical intervention, the Institute of Anesthesiology will select the anesthesia procedure that is individually adapted to you.