Bleeding occurring in the vicinity of unstable pelvic ring fractures may be difficult to control. It can be so profuse that the patient’s life is in grave danger. In these cases, the pelvis must be stabilised immediately. The urinary tract is also at risk due to its proximity to the site of the injury. Older patients frequently suffer so-called “stable fractures” (more than 50% of pelvic fractures) as a result of a fall (low-energy trauma).

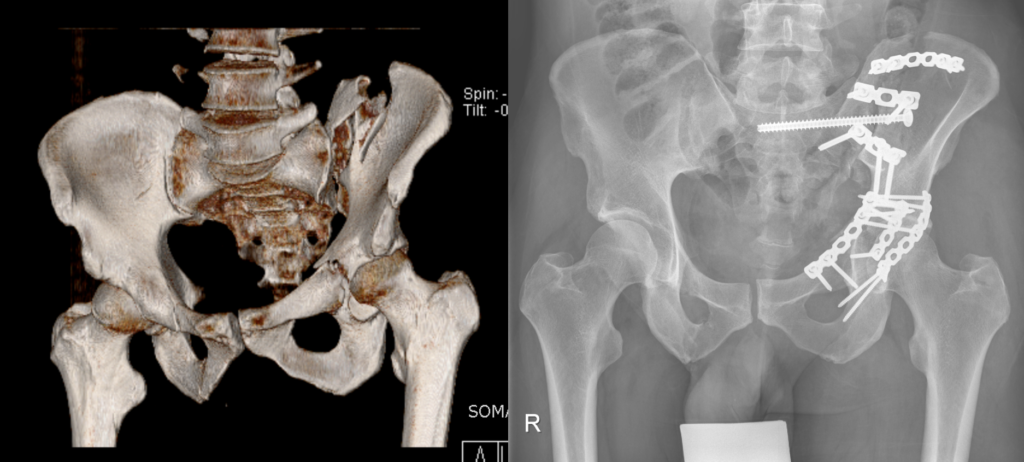

Left: 3D computer tomography following combined fracture of the pelvis and acetabulum. Right: Postoperative x-ray following fixation with plates and screws.

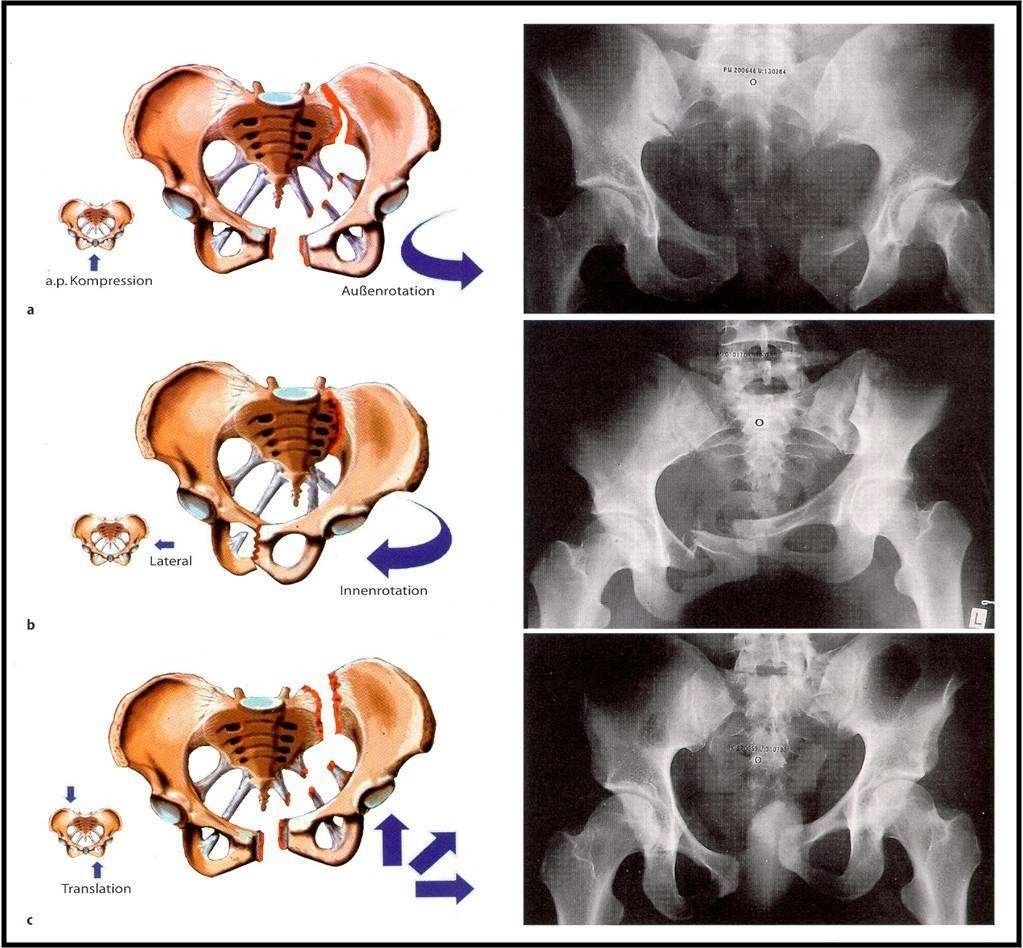

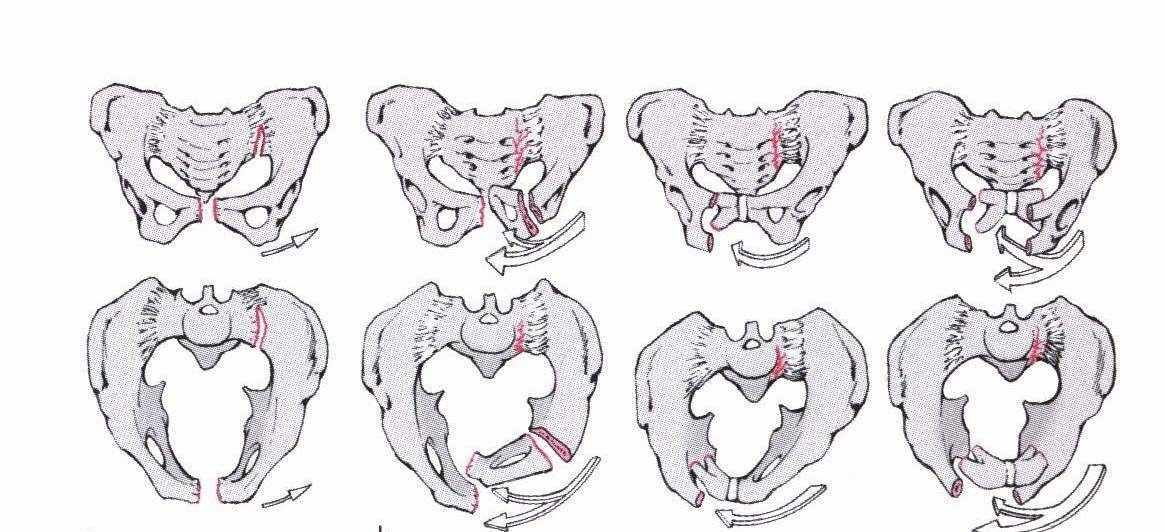

The forces involved are:

- Lateral compression

- Anterior-posterior compression

- Vertical shear (along the spinal axis)

- Combined injuries

Forces acting on the pelvis and resulting fractures (Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie up2date [Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery up2date], Thieme)

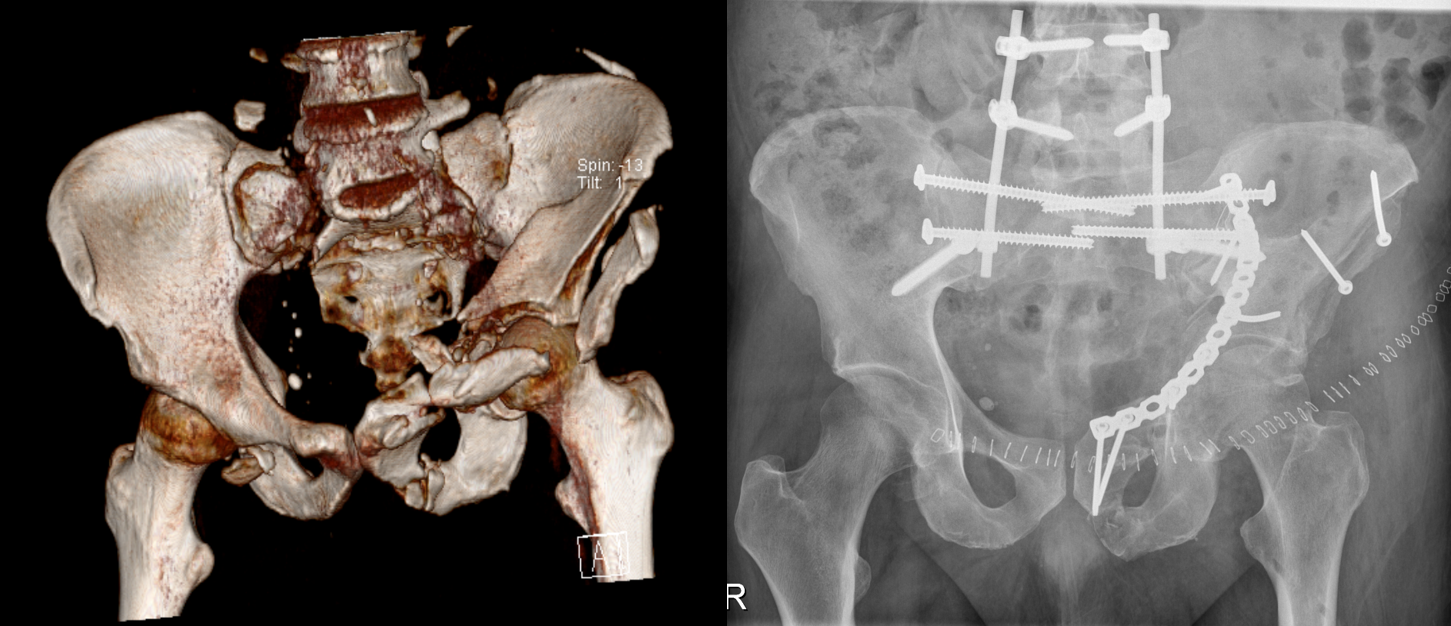

Left: 3D computed tomography imaging following an extremely severe bilateral combined fracture of the pelvis and acetabulum with separation of the pelvis and lumbar spine. Right: Postoperative x-ray following realignment of hips and pelvic ring and reconnection with lumbar spine using plates, screws and rods.

A distinction must always be made between stable and unstable pelvic fractures. Important:

- The pelvis is stable when the major structures in the posterior pelvic ring are uninjured.

- The pelvis is unstable when bony or ligamentous structures in the anterior and posterior pelvic ring have been injured.

There are various classification systems; ultimately, however, they all distinguish between stable, rotationally unstable and rotationally/vertically unstable.

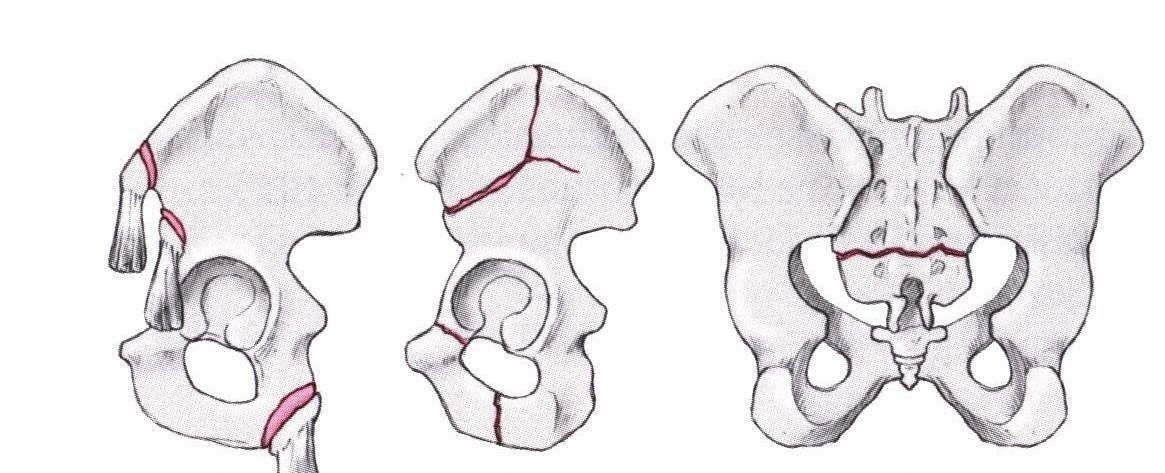

Stable injuries include fractures or avulsion of the iliac wings, ischium, pubis or coccyx below the articulated joints which do not affect the stability of the pelvic ring. These injuries can often be treated without surgery. The priorities in such cases are pain management and patient mobilisation.

Stable pelvic fractures (Ficklscherer, Orthopädie und Traumatologie [Orthopaedics and Traumatology], Urban & Fischer)

Rotationally unstable fractures (Ficklscherer, Orthopädie und Traumatologie, Urban & Fischer)

Combined injuries are the most unstable of all. They are frequently combined with additional injuries to the skeletal system and other body parts. The anterior and posterior structures of the pelvic ring are both affected. Surgery is essential in the case of rotationally and vertically unstable fractures. Depending on the injured patient’s condition, emergency external stabilisation is performed using an external or internal fixator before the definitive treatment is administered (commonly plates or screws).

Open book injury

Left: Computed tomography following avulsion injury of the first sacral vertebrum. Right: Postoperative x-ray following minimally invasive stabilisation using long screws inserted through small incisions in the skin.