Cases of pericarditis following COVID-19 infection have already been reported in the literature. Other possible causes include diseases of the immune system, rheumatologic and oncologic diseases and conditions following extensive radiation in the chest area.

Drug treatment

In the early stages of the disease, there is usually an accumulation of fluid in the pericardium. Pericardial effusion is often observed even after unproblematic heart surgery. Early drug therapy can prevent excessive fluid build-up in the pericardium. If this is not the case, the accumulation of fluid in the pericardium can lead to an impairment of the heart’s pumping function (pericardial tamponade) due to the impaired filling. In this case, the effusion must be relieved by drainage (using ultrasound guidance or surgically through a small incision at the lower end of the sternum). If the pericardium fills up again after a single drainage, a so-called pericardial fenestration may be performed in the chest cavity or abdomen – so that the fluid does not cause compression of the heart and is better absorbed in the long term.

Surgical treatment

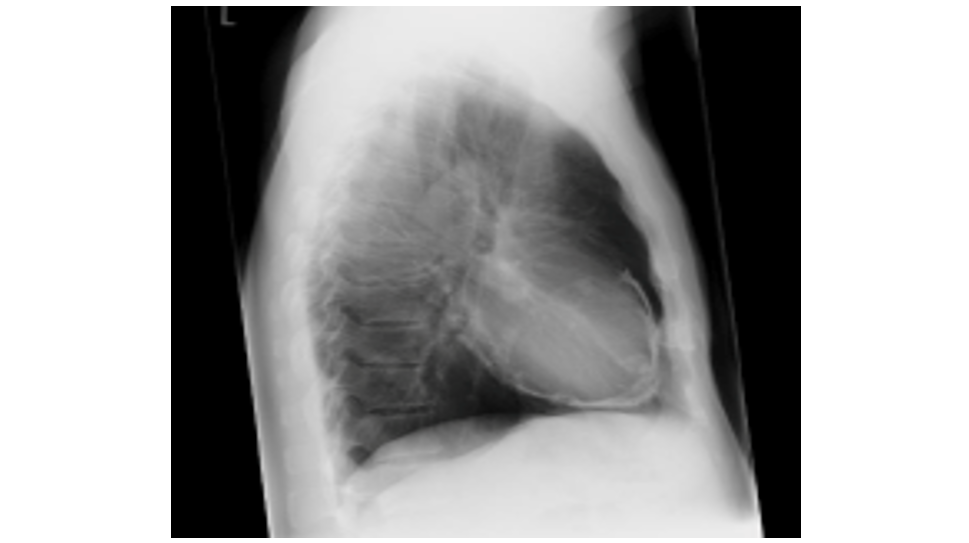

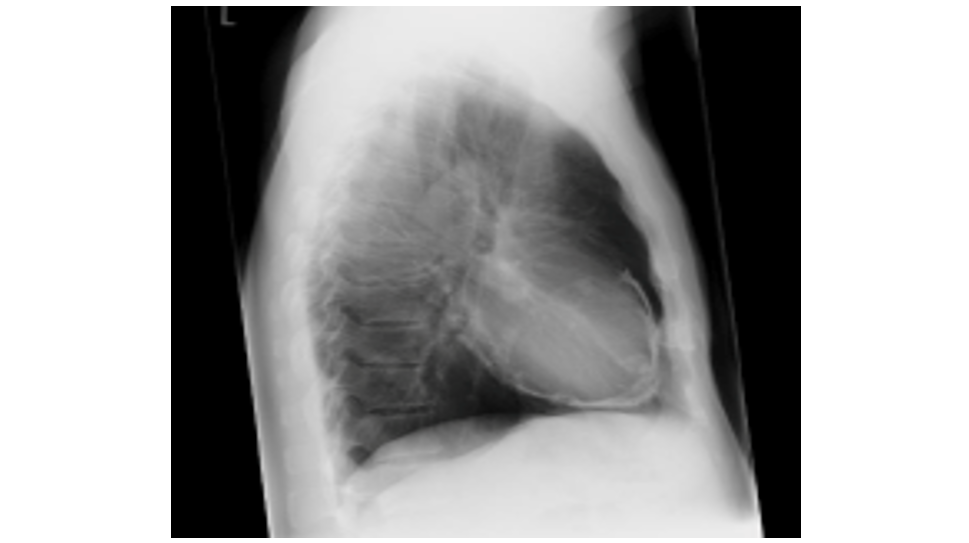

Regardless of the etiology, the inflammatory process leads to adhesions between the epicardium and the pericardium and to an increasing fibrotic thickening of the pericardial tissue. In the chronic stage, it is not uncommon for calcifications to occur, which are visible on conventional chest X-rays (see figure). These changes lead to an obstruction of diastolic ventricular filling and thus to venous congestion and reduced cardiac output. The scarring can constrict the pericardium to such an extent that the heart can no longer expand sufficiently. This is referred to as an armored heart (chronic constrictive pericarditis). In this form of chronic pericarditis with the corresponding symptoms of reduced performance (accompanied by shortness of breath, arrhythmia, feeling of fullness in the upper abdominal area), pericardectomy (removal of the pericardium) is the only effective therapy.

The procedure is usually performed through a sternotomy and can normally be carried out without a heart-lung machine. Lateral access through the ribs is considered an alternative approach. However, this approach does not allow complete relief of the constriction in the area of the right atrium and the junction of the vena cava. In older and less symptomatic patients, conservative and medicinal therapy with diuretics is in the foreground. Removal of the thickened pericardium leads to a decrease in filling pressures; this can occasionally lead to a temporary deterioration in ventricular pumping function. The short-term collapse in circulatory function can be counteracted perioperatively with medication to counteract the risk of excessive dilatation of the heart.

Typical picture of calcified chronic pericarditis.